Alluvial City: Port Towns as Regenerative Industrial Landscapes

Thesis Studio | Spring 2024 | Partner: Jose Varela | Instructors: Cordula Roser Gray and Todd Erlandson

In 1964, Fumihiko Maki proposed the concept of collective form, an architectural strategy that responds to dynamic social change rather than static, predictive urbanism. He critiqued compositional approaches, like Bernard Tschumi’s Parc de la Villette, for prioritizing graphical overlays over social engagement. Similarly, modernist megaforms, while provocative, often relied on singular, large-scale interventions that could quickly become obsolete in the face of uncertain futures.

Yet despite Maki’s critique, his own framework remained limited to formal strategies and fell short in addressing cultural or ecological specificity. This thesis reframes Maki’s theory by grounding it in the technical and temporal realities of site ecology and local culture. The result is a responsive architecture shaped over time by both human and non-human systems.

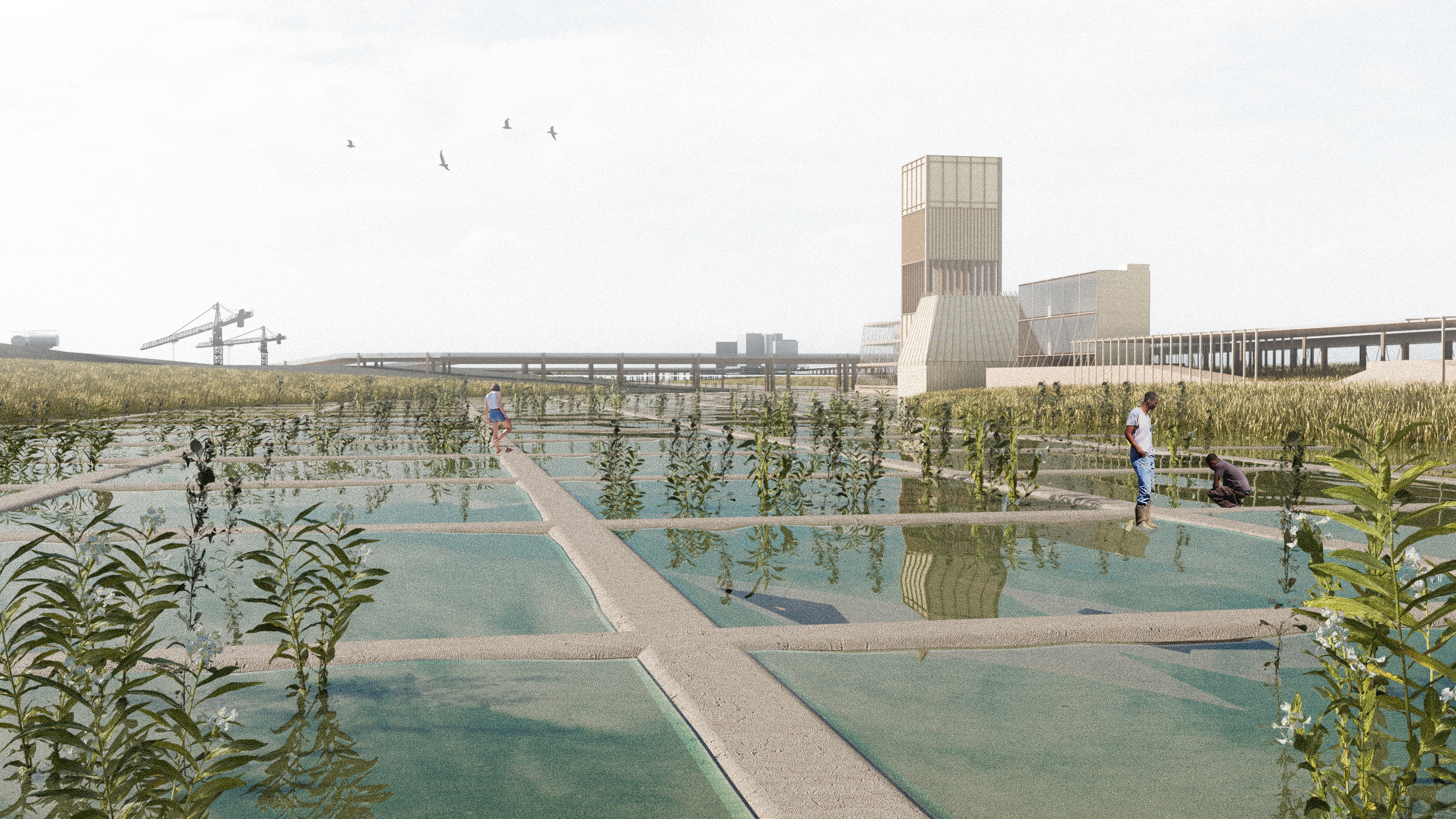

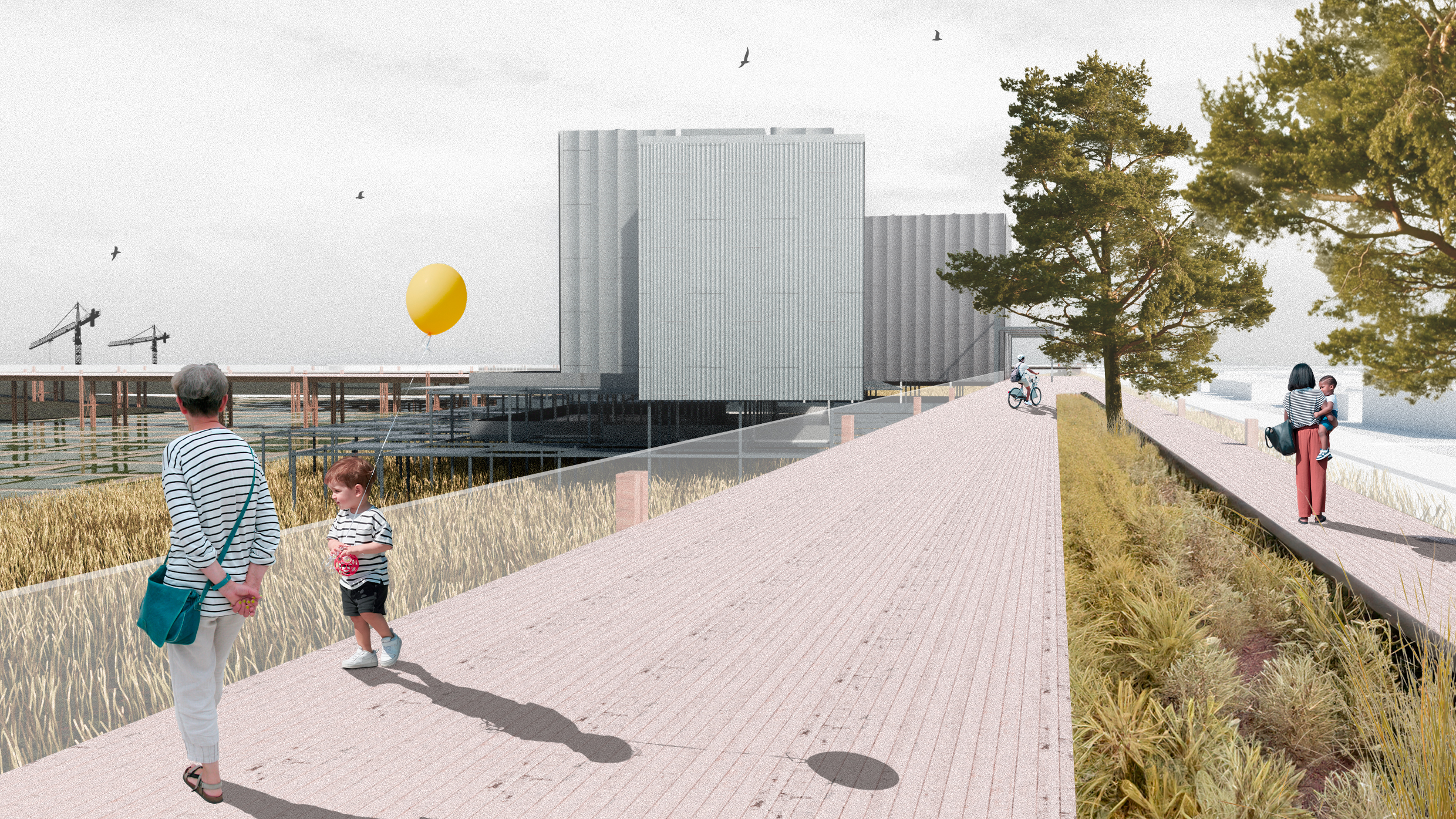

To move past the rigid boundaries that define Morgan City’s industrial maximization, urban conditions are sequentially generated, first by carving the river edge through dredging and then by river-led sediment capture. This re-scaping creates a blurred gradient of wetlands, elevated industrial zones, and recreational structures. Buildings emerge over time based on cultural needs, creating idiosyncratic objects that share a context but respond to varying needs delineated by the time they are built.

Ultimately, this process aims to transition Morgan City’s past extractivist underpinnings into a site of flattened hierarchies, allowing for symbiotic relationships between community, industry, and ecology to evolve.

Yet despite Maki’s critique, his own framework remained limited to formal strategies and fell short in addressing cultural or ecological specificity. This thesis reframes Maki’s theory by grounding it in the technical and temporal realities of site ecology and local culture. The result is a responsive architecture shaped over time by both human and non-human systems.

To move past the rigid boundaries that define Morgan City’s industrial maximization, urban conditions are sequentially generated, first by carving the river edge through dredging and then by river-led sediment capture. This re-scaping creates a blurred gradient of wetlands, elevated industrial zones, and recreational structures. Buildings emerge over time based on cultural needs, creating idiosyncratic objects that share a context but respond to varying needs delineated by the time they are built.

Ultimately, this process aims to transition Morgan City’s past extractivist underpinnings into a site of flattened hierarchies, allowing for symbiotic relationships between community, industry, and ecology to evolve.